Breed Specific Legislation - it’s time for a change

One of the RSPCA’s graphics from their #ENDBSL campaign

For the last 30-odd years, campaigners including the RSPCA, Battersea Dogs Home, Dogs Trust, the Blue Cross, and large numbers of dog professionals have all been trying to bring attention to the need for serious reform with regard to dog law in the UK - specifically surrounding the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 (DDA) [2], [4], [6], [8]. However, in the last few months and particularly this week, you may well be seeing a lot of new and revamped support for the DDA, as calls are being made (notably by the PM and Home Secretary) for a new breed to be added to the list of banned breeds, which falls under part of the DDA.

It’s easy, I think, to see why this idea is popping up, and how it’s beginning to gain traction. Clickbait headlines are a favourite for news outlets trying to keep going in the digital age, and it’s easy to feel upset and outraged at reports of injuries and fatalities as a result of dog attacks which are, ultimately, entirely preventable. However, it’s been proven in the time since the DDA was introduced in the early 90’s that Breed Specific Legislation (BSL) is not the answer.

In this blog post, I’m going to talk about what BSL is, how it’s enforced, what effect it has on dogs and owners, and why I, along with bodies like the RSPCA, Blue Cross, Dogs Trust, Battersea, as well as smaller charity organisations such as DDA Watch and Save Our Seized Dogs, feel that it is totally ineffective, and needs to be reformed.

“Every year thousands of dogs are euthanised because of the way they look”

The family dogs I grew up with as a teenager - English Bulldog Mabel on the left (as a young puppy!) stacked on top of Jazzy, my grandparents’ beloved rescue Staffie X from Battersea. And yes, that’s me next to them in the pink trousers!

What is BSL?

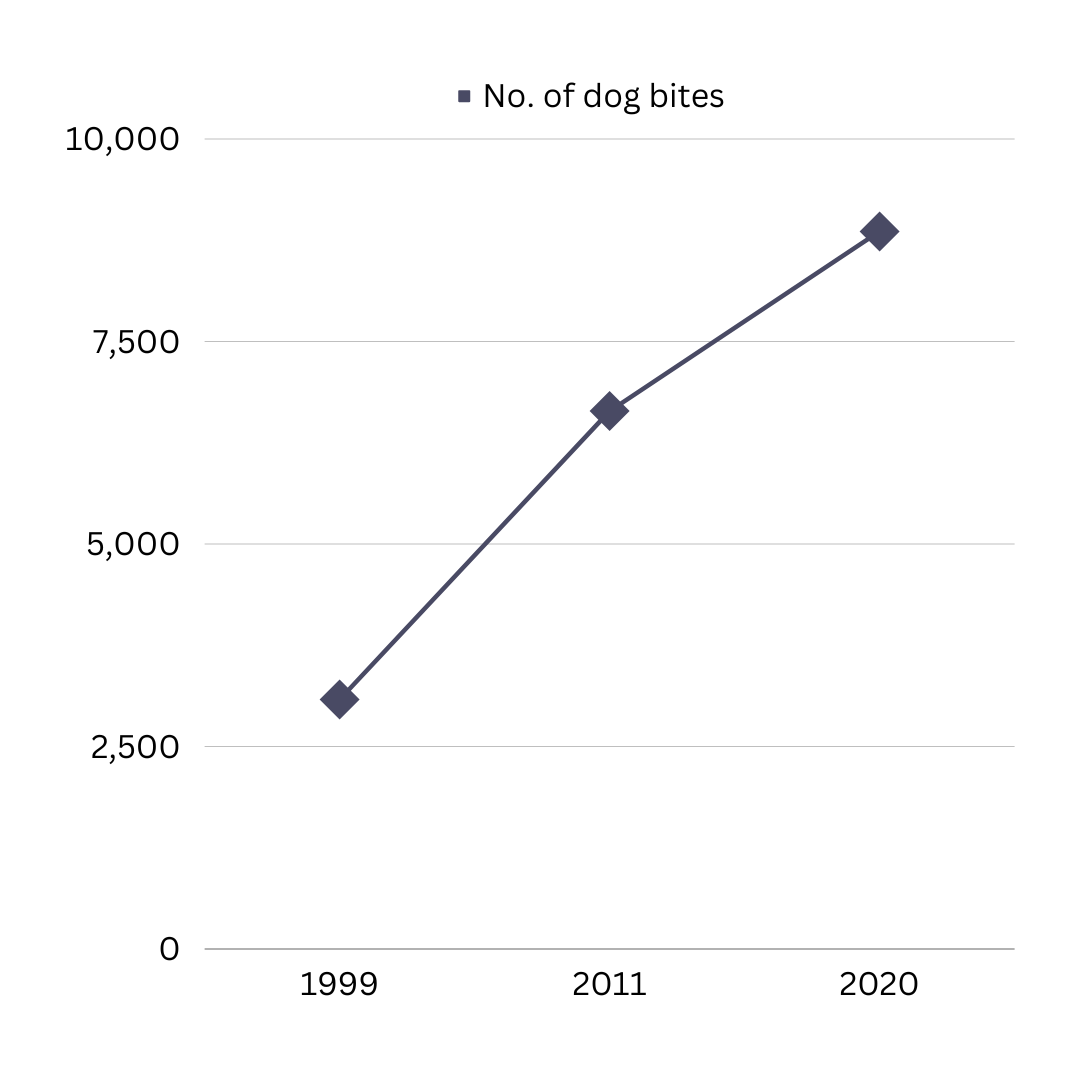

“After all this time dog bite incidents continue to rise, going from 3,079 in 1999 to 8,859 in 2020 – an 188% increase.”

“In the past 20 years (1999-2019), the number of hospital admissions for the treatment of dog bites has increased by 154%, despite the prohibition of certain types of dogs.”

So what is Breed Specific Legislation, often abbreviated as BSL? BSL was first introduced in the UK as part of the Dangerous Dogs Act of 1991, which was created in response to a number of high-profile dog attacks at this time [1]. The overall aim was to safeguard the general public, and to bring down the number of dog attacks and dog bites leading to injury or death. The portion of this legislation that is categorised as BSL is Section 1, which lists 4 types of dog that are banned in the UK.

The prohibited dog that we’re interested in for the purpose of this post is the Pit Bull Terrier Type. What’s important to note is that we’re not addressing a specific breed here that can be defined by genetics, but rather a general type of dog. The RSPCA’s 2015 report on BSL quotes,

“the term pit bull is an elastic, imprecise and subjective phrase ranging from the American pit bull terrier breed at its narrowest end through to a term which includes a number of bull breeds.” [1]

What we can gather from this is that while ‘Pit Bull’ conjures up a certain image in our minds, in reality, it’s not a term used to refer to a singular breed of dog, but rather a less formal ‘catchall’ term for dogs that share certain characteristics. The RSPCA’s report goes on to explain,

“To be identified as ‘type’, the dog is expected to approximately amount to, be near to, or have a substantial number of characteristics of a dog as described by the standard. Genetics or the dog’s parentage is not taken into account and instead focuses on appearance; any dog can be considered to be a prohibited type if its appearance is similar enough to that described by the standard. This means that a dog can be termed ‘of a prohibited type’ without sharing any genetics at all with that breed.” [1]

So, it’s got nothing to do with breed at all, rather the appearance of a dog. This means that dogs of any breed can be classed as ‘prohibited’ purely based on their looks, and in some cases this shows itself up as being a foolish metric - a case is disclosed in this report [1] in which half a litter of puppies were determined to be ‘of type’, while the other half were not - all of the dogs were siblings, so shared the exact same parentage and genetics, and presumably whatever elements of temperament might be passed down by those parents. How crazy is that?!

“The offences under Section 1 of the Act, known as Breed Specific Legislation or BSL, have been particularly controversial on the grounds that they can result, and often have, in the destruction of healthy and good-natured animals with little added protection to the public. This is because the assessment of what constitutes a “dangerous dog” under the Act is principally based on how the animal looks.”

Why were ‘Pit Bull Terrier Type’ dogs chosen for the list of banned breeds under the DDA?

The logic at this time was to ban and therefore reduce numbers of dogs originally bred for fighting - the rationale being that these dogs were physically more dangerous than other types, and inherently more likely to be aggressive. Both of these assertions have no scientific evidence backing them. This focus is made clear in the introduction to the DDA, published 25/07/1991, and quoted below:

“An Act to prohibit persons from having in their possession or custody dogs belonging to types bred for fighting; to impose restrictions in respect of such dogs pending the coming into force of the prohibition; to enable restrictions to be imposed in relation to other types of dog which present a serious danger to the public; to make further provision for securing that dogs are kept under proper control; and for connected purposes.” [16]

Here is the description given to the history of the American Pit Bull Terrier, as outlined by the United Kennel Club - one of the only Kennel Clubs to recognise the breed. Neither The Kennel Club UK nor the American Kennel Club list it as a breed.

“Sometime during the nineteenth century, dog fanciers in England, Ireland and Scotland began to experiment with crosses between Bulldogs and Terriers, looking for a dog that combined the gameness of the terrier with the strength and athleticism of the Bulldog. The result was a dog that embodied all of the virtues attributed to great warriors: strength, indomitable courage, and gentleness with loved ones.” [9]

So we can see that the background of this particular breed was certainly rooted in dog-fighting, with participants looking to create a breed that possessed desirable characteristics for this purpose. What’s interesting to note is that dog-fighting was made illegal in the UK in 1835 [10], and so ultimately the dogs being bred in this manner were exported over to the United States, where they were further honed to create what would later be called the American Pit Bull Terrier.

“The United Kennel Club was the first registry to recognize the American Pit Bull Terrier. UKC founder C. Z. Bennett assigned UKC registration number 1 to his own APBT, Bennett’s Ring, in 1898.” [9]

So, although there was some breeding of dogs of this general type in the UK, this took place predominately in the early 1800s, and would most likely have decreased following the ban on dog-fighting in 1835. Still, dogs are easily transported between countries these days, so fast forward to the 1990s, and the government felt it necessary to outright ban dogs of this ‘type’, despite no legal dog-fighting having taken place here for well over 100 years.

The idea behind this was, as previously noted, that a) dogs bred for fighting were inherently more physically dangerous than other dogs, and b) that dogs bred for fighting were inherently more aggressive or prone to aggression than other dogs. Again, neither claim has any scientific evidence to support it, and in fact evidence against these ideas has been gathered.

Even at the time during which the DDA was first implemented, it was reported that several other recognised breeds in the UK were more frequently involved with reported bites -

“Another report published by the Metropolitan Police implied that in 1991, only 34% of attacks were by pit bulls. German shepherds, rottweilers, cross-breeds and dobermanns were the next most frequent offenders.” [22]

“Each of the breeds targeted by BSL in the UK were traditionally selected for fighting. While dogs intended for fighting will have been bred and selected over generations for specific characteristics, there is no specific research to demonstrate that selection for fighting results in dogs that are more aggressive towards people than other dogs.

There’s also much focus placed on the pitbull terrier with statements made about their supposed unique ability regarding the damage and severity they can inflict compared with other breeds of dog. Again, there’s no robust scientific evidence to substantiate such claims.

Indeed, recent studies found no difference observed between legislated and non-legislated breeds in the medical treatment required following a bite, or in the severity of bite and the type of dog that bit.

We need to remember that there’s no single breed or type of dog that is aggressive and no single breed or type that is safe; all dogs are individuals.”

Here is the UKC’s description of the APBT’s characteristics, at breed standard.

“The essential characteristics of the American Pit Bull Terrier are strength, confidence, and zest for life. This breed is eager to please and brimming over with enthusiasm. APBTs make excellent family companions and have always been noted for their love of children. Because most APBTs exhibit some level of dog aggression and because of its powerful physique, the APBT requires an owner who will carefully socialize and obedience train the dog. The breed’s natural agility makes it one of the most capable canine climbers so good fencing is a must for this breed. The APBT is not the best choice for a guard dog since they are extremely friendly, even with strangers. Aggressive behavior toward humans is uncharacteristic of the breed and highly undesirable. This breed does very well in performance events because of its high level of intelligence and its willingness to work.” [9]

You can see here that although they do suggest that the breed can be more prone to dog aggression, they’re noted for their friendliness towards humans, and this is even described as something that would be an issue if you were looking for a guard dog. Bear in mind again, that this is discussing the actual UKC recognised breed, the American Pit Bull Terrier, which will be determined by genetics and parentage. This description doesn’t have anything to do with the vast majority of dogs impacted by BSL in the UK as they aren’t and don’t need to be full or part APBT in order to be considered ‘of type’. However, I think it’s interesting to note that even at this level where we’re actually looking at a specific breed which is quantifiable through genetics, we’re seeing no mention of inherent human aggression.

One popular, long-standing myth about Pit Bull Terrier Type dogs is that they have a ‘locking jaw’ - this myth has been debunked, and yet it persists. Simply put, there is no additional biological structure present in dogs of Pit Bull Terrier Type or indeed any bull breeds to allow for such ‘locking’ to occur - perhaps this myth stems more from the typical tenacity of the breed, and like many other types of dog, their unwillingness to let go of something once they’ve gotten hold of it and engaged with it. Just try playing a game of tug of war with a dog of any breed, and see what happens!

“The myth of pit bulls having locking jaws is often rooted in misunderstandings and exaggerations. Some proponents argue that pit bulls possess a "locking" mechanism due to their ability to maintain a firm grip on objects or other animals.

However, this grip is not due to any physical lock but is a result of their tenacity, determination, and instinctual drive. Pit bulls, like many other breeds, have a strong bite and an inclination to hold on when they perceive a challenge or are engaged in activities like tug-of-war.” [11]

Below, you’ll see a panel of close-up images showing dogs’ mouths, all with teeth visible.

What I’d like to highlight when looking at these images is the similarity between the mouths and the teeth on display here - don’t they all look pretty much the same? While factors such as overall size, musculature and subsequent jaw strength all of course make a difference to the overall potential severity of a bite, there is nothing here to suggest that a Pit Bull Terrier Type dog would inflict a bite any more severe than a Shepard, or a Lab, or indeed any other dog of similar or even larger size.

In honesty, severity of a bite depends on so many different factors; the context of the bite (was it inflicted by accident, was it a warning bite, what was happening around the bite?), the size and age of the dog inflicting the bite, the size and age of the person on the receiving end, and the location of the bite on the body. Any dog has the potential to bite, and any one bite could kill - all it really takes is the circumstances lining up, and that single bite being delivered with enough power to the wrong place - any major blood vessel accessible in the neck, arms and legs for instance. Depending on the factors in play, even a dog as small as a Jack Russell Terrier could potentially kill - it’s all about context.

“there is often much focus placed on the pit bull terrier with statements made referring to its unique ability regarding the damage it can inflict or that if bitten by a pit bull terrier, the injury inflicted would be much worse than most other breeds or types of dog. However, there is no scientific evidence to substantiate such claims and there has been no academic study of breed differences in bite styles. Even if studies existed for the pit bull terrier breed and such claims could be justified, it would be inaccurate to assume that the same sort of behaviour would be displayed by the pit bull terrier ‘type’.”

So has BSL really not helped at all?

Take a look at the numbers for yourself…

Graph plotting the overall increase in dog bites in the UK since the introduction of the DDA in 1991 - from 1999 to 2020, we can see a marked increase. Data extracted from [4] & [2]

“BSL was introduced in a bid to crackdown on the number of dog attacks in the UK, but NHS data shows that the number of hospital admissions due to dog-related injuries has increased since it was introduced. In the past 10 years alone, the number of admissions rose 30% from 6,640 to 8,655 (2011-12 to 2021-22).”

What we’ve seen in the last 32 years since the introduction of BSL in the UK is that the number of dog bites has actually continued to rise:

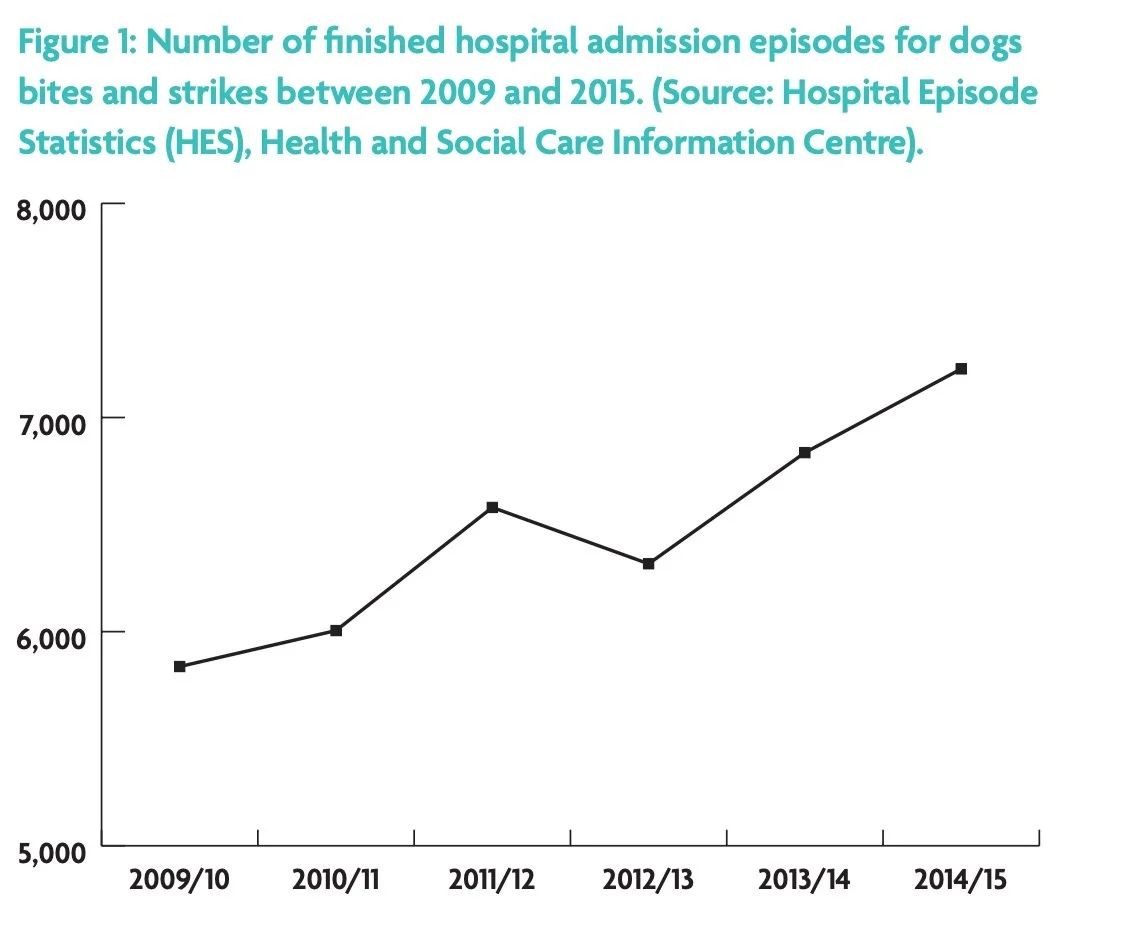

Source: The RSPCA [1]

“In the UK, an initial assessment of the DDA five years after it was enacted, found that there had been no significant reduction in dog bites. Increases in dog bites continue to occur, as shown in Figure 1. Between March 2005 and February 2015, in England, the number of hospital admissions due to dog bites increased 76 percent from 4,110 to 7,22726. There is no robust scientific evidence to suggest that prohibited breeds are a significant factor in this increase.” [1]

So, the number of dog bites continues to increase year by year, and the legislation is clearly doing nothing to stop these numbers from going up. We’ve now had 32 years to see the impact of these laws, collect data, and consider alternatives, and it’s well past time for reform.

In a motion submitted to Parliament earlier this year, it was noted that;

“the cost to the NHS of dog bites has been calculated at £777 million per year” [12]

This is is a startling number, and doesn’t even begin to take into account public spending on the side of enforcement - how much is being spent seizing, kennelling, and destroying dogs with no background of behavioural issues or bites?

“When we examine the literature, there’s no robust scientific evidence to suggest that prohibited types are more likely to be involved in dog bite incidents or fatalities than any other breed or type of dog. In terms of legal cases, between 1992 and 2019, only 8% of dangerously out of control dog cases involved banned breeds. Claims that these types of dogs pose heightened risk simply cannot be substantiated and it is both misleading and erroneous to suggest so.”

Jazzy the Staffie X with Milford as a puppy - showing him what sticks are for!

But what can we actually do to reduce dog bites in the UK?

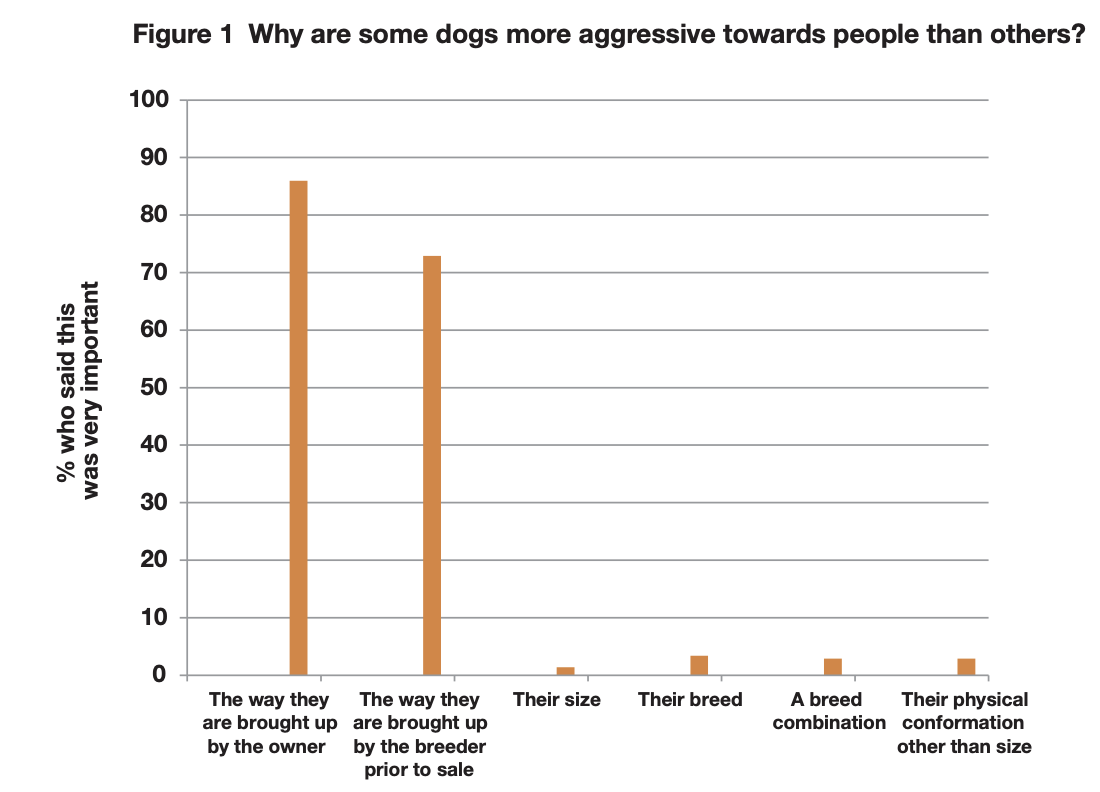

“an overwhelming 98% of expert behaviourists sugges[ed] that adding more breeds to the banned list would have no effect on reducing dog attacks”

Clearly numbers of bites aren’t dropping any time soon, and at present we’re dealing with the Prime Minister promising to make an addition to the banned breeds list - adding to the existing legislation rather than considering what changes could be made. 30 years ago, the problem was ‘pit bull type’ dogs, and in as many years Staffies were being used similarly for their appearance as status symbols, tools of violence, and intimidation. The fact that now, the problem persists but with an entirely new type of dog speaks to the root cause of that issue - it’s not the dogs, it was never about breeds, it’s about the people.

Figure taken from Battersea’s 2016 research into the relationship between dog breed and bite statistics. The figures here were taken from a survey of 215 dog behaviourists and trainers, and reflect their professional opinions. [5]

“Breed is clearly not a significant issue in determining levels of aggression. Naturally, some dogs require more stimulation and exercise and are therefore higher maintenance so their behaviour is a more acute reflection of the quality of ownership. If an owner was to neglect the basic needs of this breed of dog, it could impact on the frustration levels the dog encounters.”

Identifying the real issue

There are always going to be nasty people who want to own a dog for nasty purposes, whether it be to intentionally inflict harm on others or whether this happens through sheer poor ownership, the problem remains the same. Restricting the type of dog that these people can access does nothing to address the actual issue, which is the blatant misuse and mistreatment of dogs by these individuals.

“There are undoubtedly people who are attracted to this ‘type’ of dog for troubling reasons. For example those who use them in illegal dog fighting and those

following the trend to use these types of dogs as status symbols, presenting an image of ‘toughness’ or the threat

of aggression. Both activities often marry with poor treatment of the dog and, as with any dog, this in itself can result in aggressive behaviour. It is often pictures of these types which are featured in the media. What is presented far less often, is the large number of dogs of type which have been acquired by those who wanted a family pet, unaware that they are banned or that their dog might be judged as conforming to the standard of a

prohibited type. As a result of good breeding, rearing and positive experiences, these types of dogs are well adjusted and friendly. ”

Plenty of people misuse cars on the road - excessive speeding, driving under the influence, driving carelessly, and accidents happen every day which cause serious injury and often even death. With that in mind, we haven’t banned the use of cars - why would we?! Instead, we require drivers to pass their tests to earn their license, to take out insurance, to drive with license plates for identification, to keep up-to-date on their MOTs, the list goes on… While this doesn’t necessarily reduce the number of accidents, it does allow penalties to be put into place for committing any of these offences, and the risk of incurring a penalty or even being arrested can help to deter such crimes.

“Any dog can be a wonderful pet if trained and socialised properly, and demonising certain types of dogs is not only unfair, it is also dangerous. Breed specific legislation has failed to reduce the number of dog bite incidents, and has only served to make certain breeds of dogs more desirable to the wrong types of people, proving that action should instead focus on prevention and ‘deed not breed’.”

So, then, why are we not thinking about dog ownership in a similar way? The risks are there, and always will be. Any dog can bite; any dog could have the potential to kill. Breed has nothing to do with it, whereas proper husbandry, ownership, and handling make all the difference. Currently, the UK has NO national dog registry service, no database recording ALL incidents of injury caused by dogs, and no licensing requirements for dogs or owners. Would that not be a more sensible approach than banning breed after breed, all while the same nasty people are just moving on to the next type of dog they can readily exploit?

“Owner conduct is easier to correct through law, education or other means, which is likely to better promote owner accountability for dogs in the future. Focusing on the dog’s actions may mean it is destroyed as ‘dangerous’ while the owner can still get a new dog and act similarly in future.”

The other side of the coin is breeders. Although the law specifies that anyone advertising/selling dogs as a breeder or anyone who breeds 3 or more litters across a 12 month period must hold a license, an article diving into the UK breeding of the current breed in focus, XL Bullys, found that

“A staggering 99.7% of those advertising on Pets4Home were found to be unlicensed. Of the top kennels we examined, only one appeared to hold a council breeding licence, a legal requirement.” [24]

There’s been plenty of discussion in the last couple of years around what are often termed ‘backyard breeders’ or ‘greeders’ - essentially, those looking to make some quick cash breeding and selling pets out of their own home, with no licensing or education in dog health and genetics. It’s also alarming to consider the continued prevalence of puppy farms / puppy mills in the UK, terms used to describe breeders who churn out litters at a truly extreme rate, breeding the bitches to their absolute limit and raising puppies in very poor conditions.

Puppies sourced from puppy farms are often afflicted with health or behavioural problems as a result of their breeding and upbringing [28]. The RSPCA explains that although they are called to investigate a huge number of such breeding operations, it can be an extremely challenging and lengthy process to gather the requisite evidence to prosecute under the current law.

“In the Special Operations Unit, sometimes we can gather evidence quickly and police can obtain warrants promptly, but often it can take us many months and lots of hours of work to get enough information and evidence before we're in a position to make an official request to the police to apply to the courts for a warrant. We must gather evidence from puppy buyers and their vets, take witness statements, and seek expert input from a specialist vet who can say that the puppy sellers have broken the law.” [26]

In one case, which took 13 months of investigation before the RSPCA could apply to the police for a warrant, they,

“were able to estimate that the gang had sold approximately 439 puppies over a three-year period, turning over around £253,000.” [26]

This gives you an idea of the scale in which unscrupulous breeders are able to operate. The persons involved were utilising “21 alias names and a large number of phone numbers, email addresses and addresses” [26] and advertising online to sell these puppies. So clearly, despite efforts to legislate breeding and require licensing, people looking purely to make money from puppies continue to find ways around this.

As we all know, things changed drastically in the dog-world during and following the pandemic, and this has undoubtedly fed into existing issues such as puppy farms;

“Shortly after the UK-wide lockdown began in March 2020, the interest in getting a puppy skyrocketed. Suddenly, prices for specific dog breeds doubled and the UK market struggled to keep up. With huge profits to be made, this imbalance provided ample opportunity for people acting illegally and irresponsibly to get rich, import puppies and take advantage of innocent pet buyers.” [27]

There’s also the issue of importing dogs and puppies into the UK - something that may have a part to play with regard to the dogs currently in the spotlight, the XL Bullys which were originally bred in and imported from the United States in around 2014 [24]. Since 2020, attention has been drawn to the issues surrounding the importing of dogs and puppies, and in 2021 the UK Government made commitments to introduce the Kept Animals Bill, which in part would look at imposing tighter restrictions on the importing of dogs to the UK. However, this bill was abandoned earlier this year. As part of their initial campaign in support of this bill, the RSPCA noted that,

“From 2020 to 2021, there has been an 11% increase in commercially imported dogs, despite the cost of dogs being sold in the UK reducing since the height of the pandemic.” [27]

The risks of buying an imported puppy are similar to those tied to buying a puppy from an unlicensed breeder -

“buying an imported pet, especially one that has been smuggled, could cost thousands in vet fees and even more in emotional distress. Poor breeding and rearing can result in hidden risks such as lifelong illness, suffering and premature death.” [27]

Another issue afflicting puppies bred by unlicensed and unscrupulous breeders, be it in the context of puppy farms or ‘backyard breeders’, is high levels of inbreeding. Inbreeding is described by The Kennel Club as follows;

“Inbreeding occurs when puppies are produced from two related dogs, i.e. dogs with relatives in common. High levels of inbreeding can affect the health of these puppies, although it is difficult to know the exact impact it can have. In general, we do know that the higher the degree of inbreeding, the higher the risk is of the puppies developing both known and unknown inherited disorders. [29]”

The level of inbreeding, while not strictly regulated by bodies such as The Kennel Club or any UK legislation, can be measured by the coefficient of inbreeding (CoI).

“This calculates the probability that two copies of a gene variant have been inherited from an ancestor common to both the mother and the father. The lower the degree of inbreeding, the lower the inbreeding coefficient.” [29]

This measurement is an indicator of risk, and The Kennel Club recommends breeders take this calculation into consideration when planning a litter. In terms of restrictions, The Kennel Club will still register litters with a higher than average breeding coefficient, although they will not register dogs born of a father/daughter, mother/son, or sibling pairing other than in exceptional circumstances [29].

This, of course, takes into account breeders licensed through The Kennel Club, and dogs registered through them. The breeding coefficient for dogs reared in puppy farms, by ‘backyard breeders’, or imported to the UK from other countries, is unknown, but particularly in contexts where we see high numbers of litters being produced from the same source, it’s likely to be fairly high. When we look at XL Bullys in the UK, we see evidence of this -

“In the UK, we believe the majority of [XL Bully] dogs can trace their origins to a limited number of foundation animals. The dogs that were imported back in 2014 to 2015. Looking as far back as 5-6 generations, it becomes evident that the same dogs recur consistently in every dog’s lineage.” [24]

So clearly, not only would owners benefit from being required to hold a license and to register their dogs, anyone breeding puppies and selling puppies needs to be held to this same process. Although licensing is required for breeders, clearly this law is constantly flouted, to the detriment of the dogs produced and the often unsuspecting owners affected. This again brings us back to education - perhaps we need to turn our focus further to educating the general public on the risks of buying from unlicensed breeders, and start requiring puppies to be registered to a national database at birth, and subsequently bought with a valid registration certificate. The most actionable side of this in terms of change, in my view, would be the owners - if we can educate people and help them to make informed choices when purchasing puppies, perhaps we can begin to crack down on those trying to breed and sell dogs outside of the law.

When we look to the current questions surrounding XL Bullys, we see a lot of issues cropping up around importing and inbreeding of dogs, as well as lack of licensing [24]. Again, tighter restrictions on these elements coupled with better education and understanding for potential buyers and owners could help to cut down on the number of dogs being bred, sold, and unfortunately later affected by health and/or behavioural issues as a result of their poor breeding and early life conditions.

What I believe to be the big issue here with simply attempting to ban the breed is that again it fails to address the root issue. The article which looks into XL Bully breeding in the US and the UK [24] does not support the repeal of BSL, the reason being that the author believes that through inbreeding and lack of care on the part of breeders, the bloodlines in use have been severely tainted and can be linked to a dog with some kind of inherent issue with aggression. Although I find the information presented in this article to be useful and compelling, I cannot agree with this stance, as banning the breed does nothing to address the breeders creating and capitalising on these issues, and will do nothing to prevent the very same thing happening again further down the line - dogs bred to extremes in other countries subsequently imported to the UK and bred poorly with high inbreeding coefficients, then sold on to unsuspecting owners with no knowledge or understanding of these factors and how they may later affect their new family pet.

Ultimately, it doesn’t actually matter what the breed is, it’s the process that’s creating ‘monsters’ [24], and it’s a process that can and will be repeated unless we change something about the way importing, breeding, selling, and buying dogs works in this country.

Looking at alternative models already in place around the world

Countries such as Canada and Australia have both moved away from BSL, instead focusing on encouraging and aiding with responsible pet ownership, including licensing and identification for all dogs. At present, the public funds being wasted on seizing, kenneling, assessing, and euthanising dogs based on nothing but their appearance could be taken and put towards establishing and maintaining a national registry for all dogs, AND a national database for data on dog bites. These funds could also go into setting a standard of education and training for all dog owners - essentially, how to be a good dog owner, including how to keep yourself, your family, your dog, and those in the community around you, safe.

In Australia, specifically the state of Victoria, the distinction regarding dogs classed as ‘dangerous’ is based on deed rather than breed, as outlined in their Domestic Animals Act of 1994 [14];

“A dangerous dog is one that the council has declared to be dangerous because it has bitten or attacked a person or animal, causing serious injury or death.

The Domestic Animals Act 1994 empowers councils to declare a dog to be ‘dangerous’ if:

the dog has caused serious injury or death to a person or animal

the dog is a menacing dog and its owner has received at least 2 infringement notices for failing to comply with restraint requirements

the dog has been declared dangerous under corresponding legislation in another state or territory

or for any other reason prescribed.

Serious injury to a person or animal is an injury requiring medical or veterinary attention in the nature of:

a broken bone

a laceration

the total or partial loss of sensation or function in a part of the body

an injury requiring cosmetic surgery. [14]”

As you can see, owners of dogs deemed to be threatening or ‘menacing’ in Victoria are given warning notices and required to have a muzzle, a collar of a specific pattern denoting their status, and a lead on their dogs in public. Any owners that don’t continue to comply with this, or allow their dog to injure or kill, will have their dog declared ‘dangerous’, and added to a registry. Failure to prevent further injury or death or keeping up with restrictions on their dog then leads to strict criminal punishment for the owner;

“Heavy penalties can be applied for offences of:

attacking again

being at large

not being kept according to the law on confinement and management of such dogs.

Owners are now subject to criminal offences if their dangerous dog kills or endangers the life of someone.

Owners can be jailed for up to 10 years if their dog kills someone.

Owners can be jailed for up to 5 years if their dog endangers someone's life. [14]”

Currently in the UK, the pentalties for owners of ‘dangerously out of control’ dogs or those which inflict damage or kill are as follows:

“You can get an unlimited fine or be sent to prison for up to 6 months (or both) if your dog is dangerously out of control. You may not be allowed to own a dog in the future and your dog may be destroyed.

If you let your dog injure someone you can be sent to prison for up to 5 years or fined (or both). If you deliberately use your dog to injure someone you could be charged with ‘malicious wounding’.

If you allow your dog to kill someone you can be sent to prison for up to 14 years or get an unlimited fine (or both).” [21]

Interestingly, looking specifically at Melbourne which is the most populous city in Victoria state, it was reported in 2022 that dog attacks had increased overall since 2018 - it should be noted, however, that this reporting takes into account ALL forms of dog attack, including dog-fights and dog-dog bites, not just bite injuries received by humans.

Below is a graph plotting the data collected pertaining to this total increase in ALL dog attacks in Melbourne [13] alongside figures from the London Metropolitan Police on reported dog attacks in London [18], and the NHS statistics for hospital admissions in England attributed to dog bites or being struck by a dog [17].

- Melbourne, AU

- London, UK

- England total

- Melbourne, AU

- London, UK

- England total

There are clearly a lot of factors at play here which impact the meaningfulness of presenting this data comparatively, but I do so in order to illustrate the idea that although we can see a similarity between approaches taken in Australia and the UK in terms of the potential criminal charges that can be levelled against owners of dogs deemed to be ‘dangerous’ by their actions, the two differ in their use of BSL. The increase of dog bites reported in both locations suggests that the extra layer of BSL included within UK legislation has no additional impact on reducing dog bites - ie., it doesn’t add anything on top of what the imposition of penalties can achieve.

In the article discussing Melbourne’s rising bite numbers [13], it’s suggested that this slight increase in overall dog bites (towards dogs and humans) could in part be attributed to the increase in dog ownership numbers in Melbourne during the pandemic, and the combination of reduced opportunities for proper socialisation during this time plus lack of education and understanding on the part of many new owners.

“A 44 per cent surge in dog ownership in central Melbourne has pushed the council to commit to doubling the number of off-leash dog parks, with 20 per cent of that increase alone coming through 2020 and 2021 – the most intense years of lockdowns.” [13]

These same issues have similarly been highlighted in the UK, with the PDSA’s annual PAW Reports finding evidence of this. The 2023 Paw Report states that,

“60% of veterinary professionals say they have seen an increase in dog behavioural issues in the last two years, 57% say they have seen an increase in dogs showing signs of fear in practice, and 48% say they have seen an increase in dog euthanasia due to behavioural issues in this timeframe. Of those veterinary professionals who said they’d seen an increase in dog behavioural issues over the last two years, 75% felt this was due to lack of socialisation, 66% due to owners not being able to understand canine behaviour and communication, and 64% due to lack of puppy training.

Changes in lifestyle over the last three years due to the pandemic have led to animal welfare organisations and veterinary professionals identifying two main areas of concern for emerging behavioural problems in our dogs: separation related issues and lack of socialisation opportunities” [19]

In this same vein, the PAW Report published in the previous year, 2022, noted that;

“dogs were being left alone for longer periods of time as people returned to their workplaces and reduced the amount of home-based work hours after the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were no longer in place.” [19]

It was noted as part of this finding that such changes in lifestyle could easily have a knock-on effect for a dog’s behaviour, if proper steps were not taken to manage this change.

““We’ve had a greater number of dogs presenting post-lockdown that were chronically under prepared for changes in their lives,” said Griggs, who specialises in training high-performance working dogs and aggressive dogs.

He recommended professional training for dogs that struggle in new environments, have problems being left alone, are easily scared or worried or have high energy levels, adding the earlier the better.

“An ounce of prevention is worth 10 pounds in cure,” he said.

But Griggs believes there is too much focus on dog breeds that are “perceived” to be dangerous, and that he saw owner attitudes and behaviours as a far more predictable indicator of poor dog behaviour.

“The majority of dogs that I see with the most profound problems look exactly like 10 of the dogs you’ve passed on the street and thought nothing of it,” he said.”

So, perhaps strict penalties based on deed are not enough by themselves.

In Calgary, Canada, dog ownership hinges on licensing - owners must pay $43 to license a neutered dog, and $69 to license an unneutered dog [23]. The benefits of this licensing model are outlined in the excerpt below:

“Licensing augments traceability following dog-bite injuries, or after aggressive behaviour that stops short of dog-bite injuries (for example, chasing people in parks). People who purchase licences for their dogs contribute to society in other ways too. Due to its licensing program, Calgary has the highest return-to-owner rate and the lowest pet euthanization rate in North America” [15]

Here’s a further example from this same resource demonstrating the way in which licensing can impact traceability and accountability for dog owners;

“The case of Stella the Rottweiler illustrates the Calgary model for dog-bite prevention. Two dogs were fighting in a Calgary park, when one of the dogs bit the other dog’s companion. A bystander telephoned the city to report the incident. The bystander identified the biting dog as a Rottweiler called Stella. Within minutes, by consulting the city’s database for licensed dogs and their legal owners, a peace officer on patrol nearby could list addresses and owners for 17 Rottweilers named Stella.

After spotting a handful of potential matches, the officer reached the owner and issued fines for the dog-bite injury plus the dog fight, all the while recommending ways to stop dog-bite injuries from happening. Calgary’s database for licensed dogs allowed Stella the Rottweiler to be traced and this dog’s legal owner to be confronted and fined, all in a day’s work.” [15]

So it’s clear why this model is among those being monitored and suggested by campaigners in this country as an alternative to our current framework of BSL. Over a 23 year period, it was reported that,

“despite an increase in the population of Calgary, dog bites decreased over the period 1985 to 2008.” [1]

This therefore presents as pretty successful, given that dog bites have increased in the UK and in Australia during this time - so clearly the addition of BSL to strict penalties in the UK has had no effect, but in Canada, the use of registration and licensing has allowed for a reduction in these numbers. This could certainly point towards a scheme of this type being a good option to explore in the UK.

“When policy-makers (or journalists) call for more ambitious dog-bite policies, they tend to highlight bans and restrictions based on dog breeds. This policy approach is often called breed-specific legislation. This emphasis on dog breed is unsurprising, considering that media coverage of dog-bite injuries tends to fixate on dogs described as pit bulls.

Even so, terriers such as pit bulls were no more likely to bite people and cause serious injury than other types of dogs, including miniature or “toy” dogs, according to Calgary’s own dog-bite data. Internationally, breed bans have not consistently decreased dog-bite frequency or severity. By emphasizing dog licensing, dog welfare and a collaborative approach to public safety and enforcement, the Calgary model has achieved recognition as a viable alternative.”

Interestingly, the UK used to have a licensing scheme for dog owners - this was abolished in 1987, a move that at this time was justified by lack of subscription by the general public;

“it had long ceased to command any public respect. Less than 50% of owners bothered to register.” [20]

However, what we’ve seen since the introduction legislation around microchipping dogs in the UK is that;

“90% of dogs are microchipped – this proportion has remained unchanged for several years following the introduction of legislation making it compulsory in 2016” [19]

So clearly, over a period of 7 years, it has been possible to achieve a 90% adherence rate for a new piece of legislation surrounding dog registration and care. If this is possible, why not compulsory licensing and registration?

The RSPCA’s report [1] itself takes into account these same examples from other countries, and outlines numerous further suggestions for reform in this country, including the following:

“The UK should adopt a more holistic approach to tackling dog bites, based on education and legislation, with recognition that any dog, irrespective of breed or type, can be a safe and sociable animal or can display aggression towards people or other dogs; and that this will depend on breeding, rearing and lifetime experiences.”

“The UK and devolved governments should commit to the investigation of dog bite related incidents by suitably qualified people. All dog bites should be recorded on a centralised database with rolling analysis so evidence-based preventative measures can be identified.” [1]

It’s clear, too, from examining what data there is that improving data collection and management with regard to dog bites, be it dog-human or dog-dog, is crucial moving forward. It’s so difficult to draw meaningful conclusions about the cause of dog bites with either dogs or humans, and no data is currently collected to aid with this - recording things such as time of bite, context of bite, breed, age of dog, age of victim, relationship between dog, handler, and victim, environment in which it took place, and what the aftermath of the bite was, on a local and national level would make a massive difference to those endeavouring to find new ways forward in reducing dog bites.

The RSPCA and other major dog groups and professionals have also long been calling for a change to the way in which we educate children on interaction with dogs - what the risks are, and how to be safe around them. This could involve introducing compulsory education on the topic into classrooms on a national level, which would surely make sense as,

“NHS hospital statistics have shown, children under the age of nine years are at most risk of getting bitten” [1]

All in all, there’s a lot of room for improvement. We’re clearly never going to see these numbers fall without making changes, and yet still there’s reluctance to move away from the prejudices we all still operate under to this day - the idea that a dog that looks a certain way is inherently more dangerous than any other type of dog.

This type of thinking is dangerous in itself, as President of the BVA Justine Shotton outlines in the quote below:

“A complete overhaul of the 1991 Dangerous Dogs Act is urgently needed. Blanket targeting of specific breeds rather than tackling the root causes of why dogs act in an aggressive way gives a false and dangerous impression that dogs not on the banned list are ‘safe’ - this fails to properly protect the public or safeguard dog welfare.”

Aside from it’s obvious failings with regard to reducing dog bites and keeping the public safe, what’s so bad about BSL?

Dogs and families impacted by BSL will be affected for the rest of their lives. Dogs that are eventually judged to be ‘of type’ but granted exemption still have to live with a series of tough restrictions for the rest of their lives, being forced by law to wear a muzzle and lead at all times in public (the muzzle must even be on when travelling in the car), and failure to do so can lead to destruction of the dog. This is no way for a dog to spend their life when they have no behavioural issues requiring the use of a muzzle or to remain on lead - imagine your own dog, or your friend’s or family member’s dog being forced to wear a muzzle day-in, day-out, just based on their appearance when they have no background whatsoever of causing or threatening harm to anyone. Muzzles and walking on lead can be very important for dogs who require these tools and restrictions, but it’s unfair to impose them onto dogs with no existing issues.

What’s even more heartbreaking is that this outcome is actually one of the best that anyone impacted by BSL can hope for. Many dogs seized as part of BSL are euthanised after being deemed ‘of type’ but not fit for exemption based on other factors, which can and often do involve the owner’s situation, as the restrictions on owning a dog deemed a prohibited type are equally strict and difficult to navigate. Depending on your housing situation, you may find that you are unable to live in your current rented accommodation once your dog has been judged ‘of type’, or the officers and judges assessing your case may deem your family unfit based on having young children, or simply based on how fit they find you to be as a person. Unfortunately, when judging this they can even take into account the way you react to officers coming to seize your dog, which obviously would be a scary, confusing, and upsetting experience [22].

There’s often a sense of ‘they should have known better’ when individuals are charged with offences such as owning a banned type of dog, however as we have seen, perfectly legal pure or cross breeds can be judged as ‘banned’ based on nothing other than looks, which has nothing to do with their actual breed or genetics. So, a family pet adopted from a shelter or bought from a breeder as a legal breed could further down the line be seized even though the family had no idea that their pet could be considered illegal.

“In practice... a range of legal pure and cross breeds can be identified as illegal dogs if they look close enough to the standard. In applying the law, the welfare of many dogs has been unnecessarily compromised due to the requirement for seizing and kennelling as well as the conditions imposed on dogs who are allowed to be legally kept. Furthermore, thousands of prohibited dogs have been needlessly euthanased as it’s not possible to rehome prohibited dogs to new owners.”

A big issue and another hardline restriction of BSL is that dogs ‘of type’ cannot be transferred to new owners unless their current owner dies or becomes seriously ill. This means that if your family is judged unsuitable for your dog based on the court’s assessments, the dog cannot be rehomed and would have to be euthanised. This also means that rescue centres who take in dogs and later discover them to be considered ‘of type’ have no other option but to euthanise perfectly healthy, well-behaved dogs of any age because they would have no ability to place them into a home at any stage in their lives.

“Duncan was brought to us as an injured stray. Unfortunately, the Status Dogs Unit (SDU) confirmed he was of type and would have to be euthanised after serving his stray days.

Our team who looked after Duncan described him as a gentle giant who was very well behaved. He knew basic commands and, if he been another type of dog, would had made a great companion to someone. The law meant Duncan was denied that chance.”

Dogs seized under BSL suffer regardless of the eventual outcome - this is something that has been noted by studies into the impacts of BSL, including the RSPCA’s report, with an excerpt below outlining statistics, as of 2015, on how long the average dog seized under BSL would spend kenneled while proceedings took place.

“on average it took 186.4 days to prosecute a s1 offence and 61.2 days to exempt a s1 dog. It is very likely that dogs seized and kennelled as a result of BSL, even for short periods of time, may find it difficult to cope with kennel life.” [1]

Although presumably timelines will have changed since 2015, we can see that generally this is not a short process. If you’ve ever visited a rescue centre with kenneled dogs, or a boarding kennel, you’ll no doubt have observed that it can be a bit of an intense environment - and that’s just from our perspective! With lots of dogs confined within an overall large area, but with little space to themselves, kennels tend to be noisy, and this can severely impact a dog’s ability to rest properly, which is critical to their overall health and wellbeing.

Dogs in kennels, particularly those kenneled under BSL, have reduced contact with other dogs and with humans, and this too can be detrimental to their mental wellbeing, which can then have a knock-on effect on their behaviour. It should also be noted that owners of seized dogs are not allowed to visit their dogs at all during this lengthy process - the location in which their dog is being held is not even disclosed at any time.

Furthermore, cases have been reported in which dogs have been deemed unsafe for officers or kennel staff to handle, and in these instances dogs may be left in their kennels with no human contact, and without being removed for exercise - one such notable case involving a dog who was kenneled under BSL for 2 years, and was not exercised or handled at all during this time [1]. This takes out all opportunities for any enrichment and engagement they might otherwise receive outside of their kennel, at further detriment to their overall wellbeing. The assessments that lead to these conclusions often don’t take into account the circumstances of the dog’s arrival into these conditions, whether they’ve had any help adjusting to their new circumstances, and whether the dog had any prior history of behavioural issues towards humans prior to assessment.

“Research using dogs kennelled for a variety of reasons has shown that many animals find kennel life challenging and experience poor or compromised welfare as a result. Studies have also shown that there are specific aspects within the kennel environment that, if inadequate or inappropriate, make it difficult for dogs to cope. For example, high levels of noise, a lack of environmental enrichment, small kennel sizes and restricted exercise may influence dogs’ behaviour patterns and can limit their ability to perform strongly motivated behaviours such as resting, playing, exploring and investigating.” [1]

What can we do now?

I hope that after reading through this post, and taking a look into the linked references below, that you might agree that BSL is an ineffective, and outdated approach to legislating dogs and to protecting the public. It’s clear from data gathered and analysed by numerous experts and groups over the last 32 years that the current legislation doesn’t work - it hasn’t reduced dog bites, it hasn’t done anything to improve education around ownership and dog safety, and instead has simply directed a lot of money towards seizing and destroying perfectly good dogs with no behavioural issues or history of violence. This approach does nothing to tackle the real issue, which has far more to do with attitudes towards ownership, improper breeding practices and lack of restrictions on importing animals, lack of licensing and registration for ALL dog owners, and lack of education around dog safety in the UK than it has to do with any one dog breed.

My advice now? Keep a level head - it’s easy to make XL Bullys the next target of our cultural prejudice against bull breed dogs, and to hope and imagine that a quick ban would solve the issue in front of us - but the evidence is here. We already have the roadmap to show us what happens in the wake of BSL. Following the introduction of BSL in the 90s, thousands of dogs were euthanised, and thousands continue to be euthanised each year - yet this has done nothing to drop dog bite numbers, and nothing to safeguard the general public. If we allow the same thing to happen to another generalised group of dogs, we’ll be making the same mistakes made 30 years ago, leaving the root of the issue unaddressed, and the same people determined to misuse and exploit dogs for their own gain free to simply move on to dogs of another breed, another type. All the while, the general public remain under the false impression that dogs of other breeds are safe, and owners will continue to neglect socialisation efforts and training.

Any dog can bite; any dog can kill. Any dog can be destroyed based on how it looks, while the handler responsible for its poor treatment, poor socialisation, and lack of care and control, is free to move on and repeat the same process on another dog. If we ban XL Bullys, we won’t be solving the problem, we’ll be continuing to look the other way. We need legislative change NOW, and now more than ever support for campaigns to end BSL is critical.

What you can do today is show your support.

Like and follow charity groups dedicated to campaigning against BSL, and providing support to families and dogs affected by BSL - DDA Watch and Save Our Seized Dogs. You can sign petitions shared by these groups, and write to your MP using templates made available by them, or by the big names also backing the end of BSL - The RSPCA, the Blue Cross, Dogs Trust, and Battersea.

You can further support groups such as DDA Watch and SOSD with donations, as both groups help to raise money for the appeals and assessment processes for dogs that have been seized under BSL. You can read more about this work on the Facebook pages or websites for both groups, and keep up to date with funding drives, raffles, and other events hosted by either group.

You can share information on BSL with your circle - a lot of people aren’t aware of the full extent of this legislation, and of the impact it has. You could share this blog post, or any of the linked resources below with friends and family, and help to spread the word.

Lastly, I’d like to challenge everyone reading this to reflect on their own perception of certain types of dogs, and how we interact with them in the real world. When encountering a bull breed type dog, consider your reactions - how do you feel about the interactions between yourself / your dog and this type of dog, and would you feel that way about this dog if it were a different breed, eg. a spaniel or a labrador? Does your perception of its behaviour change when you change the breed, or is it really unruly and out of control?

I think that sometimes it’s easy to let our preconceptions about certain breeds cloud our judgement, particularly when we’re living under legislation that reinforces the idea that certain breeds are inherently more dangerous than others. So, where we might encounter a young, playful bull breed dog and find them a bit full on and a bit intimidating, we might then encounter another dog behaving the same way but find it less scary or offputting because it’s a breed we are more comfortable with, and are likely to give a little more leeway to.

It’s also my view that communication and help within the community can be so much more valuable a tool than reporting and policing when it comes to issues with dog behaviour and ownership. Of course, if you are dealing with a dog that is genuinely dangerously out of control, then I’m not saying that proper authorities shouldn’t be utilised, but rather that if you encounter somebody who you can offer some advice and guidance to, then take the opportunity to do so. If we report and remove dogs from owners within the current legislative framework, this does nothing to address issues with ownership or to assist that person with future dogs - therefore the same mistakes can simply be repeated. If we can start to operate on a basis of educating and informing first, we have a chance to help change somebody’s life for the better, and therefore the lives of everyone in the community.

References

[1] https://www.rspca.org.uk/webContent/staticImages/Downloads/BSL_Report.pdf

[2] https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/how-we-help/stories/end-bsl

[3] https://www.animallaw.info/intro/canadas-dangerous-dog-law

[4] https://www.battersea.org.uk/what-we-do/animal-welfare-campaigning/breed-specific-legislation

[5] https://bdch.org.uk/files/Dog-bites-whats-breed-got-to-do-with-it.pdf

[6] https://www.bluecross.org.uk/our-campaign-to-end-breed-specific-legislation

[8] https://www.rspca.org.uk/-/blog-why-bsl-is-failing

[9] https://www.ukcdogs.com/american-pit-bull-terrier

[10] https://www.rspca.org.uk/whatwedo/endcruelty/investigatingcruelty/organised/animalfighting

[11] https://www.k9magazine.com/pit-bull-locking-jaw-myth/

[12] https://edm.parliament.uk/early-day-motion/60889/dangerous-dogs-act-1991

[16] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1991/65/introduction

[19] https://www.pdsa.org.uk/what-we-do/pdsa-animal-wellbeing-report/paw-report-2023/dogs

[20] https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/RP98-6/RP98-6.pdf

[21] https://www.gov.uk/control-dog-public#:~:text=Penalties,or%20fined%20(or%20both).

[22] https://www.saveourseizeddogs.org/podcasts-and-presentations

[23] https://www.calgary.ca/pets/licences.html

[25] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2018/486/schedule/6/made

[26] https://www.rspca.org.uk/whatwedo/endcruelty/investigatingcruelty/organised/puppyfarming

[27] https://www.rspca.org.uk/getinvolved/campaign/puppytrade

[28] https://deanfarmtrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/DFT_RunforFreedom_WK05_puppy-farming_01.pdf